Everyone has heard of Alexander the Great, who conquered the ancient world from Epirus in Greece all the way to India, creating the culture that would later be taken over by Rome. But the first three historians in history all built their narratives around kings named Alexander and places called Ephyra long before “the Great” one lived. If history literally rhymes and does not repeat itself, then all historians must be poets (at best). Indeed, it seems that Western history is just a long series of remakes.

The first historians were Homer, dated to 700 BC, Herodotus, dated to 440 BC, and Thucydides, dated to 400 BC. Homer’s Iliad is an obviously mythological work that tells the story of a Trojan prince named Alexander (aka Paris) who kidnaps Helen from the kingdom of Argos and the Greek islands. Helen is the most beautiful woman in the world and the very namesake of Greek identity. We call Western culture Graeco Roman because Alexander the Great is credited as being Greek and the champion of Hellenism. Yet in Homer, Alexander (Paris) has stolen Helen and taken her to Troy.

This argument takes an incredible step further, linking Alexander (Paris) to Croesus the first Lydian emperor, and thus also to Cyrus, Christ, and the Caesars. According to experts, there is no connection between Paris, the nickname or title of Alexander in the Iliad, and “Parisii”, the Celtic tribe who gave their name to the capital of France. But the etymology is parallel, making it no surprise that a Phrygian lord would be called Paris. Wikipedia says of Parisii, “Alfred Holder interpreted the name as 'the makers' or 'the commanders', by comparing it to the Welsh peryff ('lord, commander'), both possibly descending from a Proto-Celtic form reconstructed as *kwar-is-io-.”

This reconstruction is nearly identical to the Lydian emperor Croesus (Krowisas in Lydian), who conquered the former lands of Phrygia circa 585 BC. Phrygia also became known as a Celtic stronghold after 279 BC in the wake of Alexander the Great, and Troy was originally a Phrygian city. Thus Paris and Croesus appear to be the same proto Celtic name or title. Phrygia became known as Galatia in the Roman era, as “Gallic Hellenes” flourished in Anatolia. As we shall see, Polybius proves that Galatia is connected directly to Galilee and signifies the same Celtic identity.

Furthermore, since the Persian emperor Cyrus is a literary doppelganger of Croesus and his name is an Old Persian transliteration (Kurus) of the same, and since Cyrus and Croesus, traveling together, were known for creating an empire from Greece to India in fashion similar to the legendary munificence of Alexander, it becomes possible that all these histories are about the same “Paris”, the same lord, and the same conquest, projected into the past by industrious scribes. Herodotus says Cyrus literally had Croesus on his funeral pyre before sparing him and becoming buddies.

Herodotus and Thucydides also introduce the story of Alexander I, king of Macedon, and his son Perdiccas who play central roles in both the Persian and Peloponnesian wars long before Alexander the Great. One of the biggest red flags of ancient history is that the authors proceed like clockwork. Herodotus resumes centuries after Homer, then Thucydides picks up exactly where Herodotus leaves off, and our next historian, Xenophon picks up exactly where Thucydides leaves off. Furthermore, these are the only available histories for the eras they describe.

We can see how all three Alexanders are associated with the enemies of Greece: Paris hails from Troy, Alexander I supports the Phrygian army led by Persia, and his son Perdiccas continually exacerbates the Peloponnesian war in Greece. Thucydides even remakes scenes from Herodotus in his Peloponnesian War. Almost a century after Thucydides, Alexander the Great’s father Philip defeated Greece first of all before his son went to Asia. That’s the first four big wars of Western history: Trojan, Persian, Peloponnesian and Alexandrian, all featuring adversaries named Alexander.

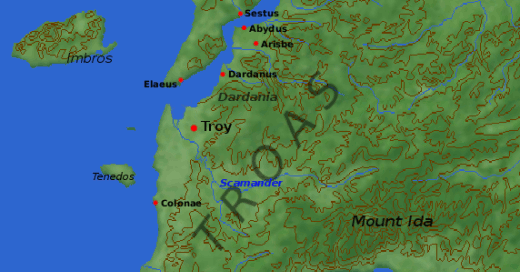

Yet there is still a wide gulf between “Paris” Alexander and Alexander the Great. The former was the enemy of Hellenism, and the latter was its champion. One of our great insights is that Homer’s Iliad does not actually place Mount Olympus in Greece at all - he places it above the plain of Troy, north of Apollo’s temple in Pergamum. In other words, the original Olympus of Homer is Mount Ida in modern Turkey, the sacred mountain of the Phrygian mother goddess Cybele. Olympus is even called Ida by Zeus in the Iliad. Furthermore, the Iliad places the Greek kingdom of Argos amidst Ephyra and Thessaly - in other words, in Epirus and Macedonia, not the Peloponnese.

1. Homer’s Alexander and the Hellenes from Epirus

The fantasy of Homer is that his works are ancient oral traditions put into verse and meter by a lyrical genius. His genius cannot be contested, but just because a work of literature takes on the trappings of the distant past does not mean that it hails therefrom. Like all texts, Homer could be a purposely contrived fiction.

The Trojan war in Homer mythicizes the invasion of the “Sea Peoples”, also known as the Bronze Age collapse, Dorian invasion, or Return of the Heracleids. Wikipedia says that by 1150 BC Mycenean architecture in Greece was abandoned, and “the Hittite civilization also suffered serious disruption, with cities from Troy to Gaza being destroyed”. Around 1175 BC, the Philistines or Palestinians landed in Gaza with their new iron technologies. Bronze Age Troy was destroyed about 1180 BC. Coastal city states north of Palestine, later called Phoenicia, soon invented the alphabet.

In Anatolia, where the Hittites had ruled, the antecedents of Hellenic culture flourished, including Troy and Phrygia. Hellenic Troy was built in this prehistorical period, circa 700 BC, the same time as the first Hellenic style temple further south in Ephesos, and Troy was destroyed again circa 85 BC by Rome. The Iliad officially dates to 700 BC, describing the events of centuries earlier. But could it be an anachronism?

Simon Pulleyn’s analysis of the Iliad reveals an artificial mish mash of dialects that does not match up with any other ancient Greek languages:

“Homer’s dialect (the ‘epic’ dialect) differs from others in that it was never the spoken language of a particular community. It is, rather, an artefact specifically moulded for the composition and transmission of epic song. This artificiality is apparent in three ways: (1) the mixture of elements from different dialects […] (2) the retention of linguistically ancient forms alongside more recent ones […] and (3) modification of regular grammatical forms to make them fit into a hexameter […] No other historically attested Greek dialect exhibits al these tendencies together on such a scale.”

-Simon Pulleyn, Homer: Iliad I

Homer is the first to ever mention the city of Ephyra, which as confirmed by Thucydides, must be the namesake of Epirus. Homer writes of soldiers “commanded by Tlepolemus, son of Hercules by Astyochea, whom he had carried off from Ephyra, on the river Selleis, after sacking many cities of valiant warriors” (Book 2). Apollodorus later claimed that Astyochea was the mother of Troy’s founder.

Homer writes of Ephyra, “there is a city in the heart of Argos, pasture land of horses, called Ephyra, where Sisyphus lived, who was the craftiest of all mankind”. Argos is the kingdom Agamemnon and Menelaus from which Paris Alexander takes Helen, and it is also claimed by Herodotus to have been the origin of the Macedonian kings, who were the neighbors and lovers of Epirus. Homer also says a prince from Ephyra named Bellerophone was sent to Lycia south of Phrygia, and his descendants became Trojan warriors (Book 6). Thus Homer connects Epirus to both Argos and Troy.

It is a big problem that Homer tells us Ephyra is in the heart of Argos, because Argos is supposed to be between Athens and Sparta, and the city known as Ephyra is in Epirus, north of the Peloponnese on the Greek mainland. The Iliad says the “Greek” kings came from Argos; in book 1, Agamemnon speaks of “my house at Argos”, and in book 3, Alexander (Paris) speaks of his adversaries going “home to Argos and the land of the Achaeans”. Homer calls Argos the “wealthiest of all lands” (Iliad 9).

Otherwise Homer’s geographic exposition is slim; he calls Hellas, homeland of Helen, the “land of fairwomen”. Homer’s Iliad uses the word Achaean 583 times, Argos or Argive 177 times, Aetolia 15 times, Hellas or Hellenes 7 times, Athens and Sparta both twice, and Peloponnese and Greek never. He mentions Pelops “the mighty charioteer” in a single sentence, whose divine sceptre is later “borne by Agamemnon, that he might be lord of all Argos and of the isles” (Iliad 2). In the Homeric sequel Odyssey, Menelaus speaks of “making a tour in Hellas or in the Peloponnese”, indicating that the Peloponnese is not Hellenic, despite the fact that it is supposedly the homeland of Argos and Helen (Odyssey 15).

Furthermore, when Homer says “pasture land of horses, called Ephyra”, he invokes association with Thessaly, neighbor of Epirus and Macedonia, reknowned for its horses. Alexander the Great rode a giant Thessalian steed named Bucephalus. The evidence leads us to conclude that the Iliad is actually about a war between Epirus and Troy. This should not be surprising since Mount Olympus is in the same region on the border bweteen Macedonia and Thessaly, while Alexander the Great’s mother was an Epiru princess named Olympias. What is surprising is that Homer actually places Mount Olympus above the plains of Troy, not Greece.

During the fighting outside the walls of Troy, Hera (Juno) looks down on the fighting from Olympus: “Juno of the golden throne looked down as she stood upon a peak of Olympus and her heart was gladdened at the sight of him who was at once her brother and her brother-in-law, hurrying hither and thither amid the fighting” (14). The Iliad’s placement of Olympus in the Troad and not Greece is made explicit when the mountain is called Ida; for example, both Hector and Ulysses pray to the highest God: “Father Jove, that rulest from Ida, most glorious in power, grant that he who first brought about this war between us may die, and enter the house of Hades, while we others remain at peace and abide by our oaths” (3).

And just as Olympus is Ida, the Iliad tells us the temple of Apollo is in Pergamus, near Troy: “When, therefore, Minerva saw these men making havoc of the Argives, she darted down to Ilius from the summits of Olympus, and Apollo, who was looking on from Pergamus, went out to meet her; for he wanted the Trojans to be victorious.”

Alexander (Paris) likewise sallies forth from Apollo’s city of Pergamus:

“Paris did not remain long in his house. He donned his goodly armour overlaid with bronze, and hasted through the city as fast as his feet could take him. As a horse, stabled and fed, breaks loose and gallops gloriously over the plain to the place where he is wont to bathe in the fair-flowing river—he holds his head high, and his mane streams upon his shoulders as he exults in his strength and flies like the wind to the haunts and feeding ground of the mares—even so went forth Paris from high Pergamus, gleaming like sunlight in his armour, and he laughed aloud as he sped swiftly on his way.”

Iliad 6

The question becomes, if the Iliad is about a war between Epirus and Troy, with Alexander playing the role of oriental villain, why does Herodotus turn Alexander into a Macedonian king, a neighbor of Epirus and the Thessalian horselands? Why does Herodotus claim that the kings of Macedon came from Argos? Why did Alexander the Great have an Epiru princess for a mother, and why did he play the role of a Greek hero who carried Hellenism over the ruins of Troy? How did he go from eastern villain to western hero? And why does he have so much in common with Croesus/Cyrus/Caesars/Christ? Everything may hinge on an Epiru city called Phoenix.

Since Homer himself links Epirus with Troy by way of Bellerophon, is becomes clear that the Trojan war was a civil war as much as anything else. Indeed, the Iliad is a war among the Gods themselves. In a conversation with Zeus, Hera boasts her three facorite cities “are Argos, Sparta, and Mycenae. Sack them whenever you may be displeased with them. I shall not defend them and I shall not care” (Book IV).

2. The Two Alexanders of Herodotus

Herodotus takes us as far back as possible from his lifetime, to about 550 BC, to tell the next chapter of Greek history that supposedly took place several centuries after the Trojan war. As the first to treat the past in the name of journalism and not poetry, Herodotus is considered the actual father of Greek history.

But Herodotus is hardly less concerned with myth and moralization than Homer. Herodotus openly used Homer as a source, and begins his book by casting moral aspersions on Troy, saying “the Trojans perished in utter destruction” so that “they might make this thing manifest to all the world: that for great wrongdoings, great also are the punishments from the gods” (History 2:120). While the historians get less mythological over time, they are all opinionated moralists. As Herodotus claims, “when I do mention the gods, it will be because my history forces me to do so” (2.3).

Translator David Grene writes of Herodotus, “it was during his childhood that the Persians had twice been driven back, against all the odds, thanks, he now realized, largely to the the moral and political leadership provided by the Athenians. This was a heroic tale, not only of heroic individuals, as in the Trojan War, but of the city-state, and it would soon be lost from memory unless it was fixed in writing.” Thus we can see that while Homer heroicized Argos, Herodotus heroicizes Athens.

Grene writes, “the broad lines of The History are shaped like those of a Greek tragedy. But it is never an acknowledged artistic fiction”. He says of Herodotus’ work, “the solidity is not that of reconstructed and verifiable fact but of the interaction between experience and dreams”. Furthermore, “it is remarkable how much of Herodotus’ presentation of history openly deals with its illustrative or even pedagogic value for human happiness or its failure”. Obviously, Herodotus is another mythmaker.

One major divergence between Herodotus and Homer is that Herodotus says Alexander (Paris) was blown off course to Phoenician Egypt after stealing Helen from Argos, landing at a place called the “Tyrian camp”. Egyptian priests claim Alexander landed at the mouth of the Nile at an old shrine of Heracles (History 2:112-13). This is the same location as the city of Alexandria founded by Alexander the Great! In Herodotus, Alexander’s servants rat him out to the Egyptians. The Egyptian judge says he would have killed Alexander for his crimes against Greece if he were anything other than a stranger wrecked by a windstorm. Herodotus says Helen stayed in Egypt throughout the Trojan war, and that Homer secretly knew this.

Herodotus situates himself chronologically by saying Pan was born “after the time of the Trojan wars and about 800 years before my time” (2.145). Aside from Alexander who was Paris who wanted “a wife from Greece by rape and robbery”, Herodotus tells us about a second Alexander, “the seventh in descent from Perdiccas, who created the Macedonian monarchy”, known to history as Alexander I or Alexander the Philhellene.

This second Alexander ruled from about 498 BC and was known as the first Athenian proxenos, a role characterized by Herodotus as “Consul and Well-Doer for the Athenians” (History 8.136). Herodotus says that Macedonia was formed after three brothers were banished from Argos to Illyria (just north of Epirus). The youngest of these brothers was a wise and ominous shepherd named Perdiccas. Perdiccas and his brothers flee from the Illyrian king, and are saved when a river miraculously rises after they cross it. Thus Herodotus says “There is a river in that country to which descendants of those men from Argos sacrifice as their deliverer”. The brothers settle in Macedonia near the “gardens of Midas”, the most famous of Phrygian kings.

Alexander I, seventh generation descendant of Perdiccas, plots to kill a delegation of Persians by disguising young men as women to seduce the Persians: “Alexander put alongside each Persian man one who seemed in truth a woman, and when the Persians tried to feel them, the young men struck them dead”. He then escapes justice by marrying his sister Gygea to a Persian general (History 5.20-21). Wikipedia wisely notes “this story is widely regarded as a fiction invented by Herodotus”.

Herodotus tells us two more anecdotes about Alexander I that would be adapted by Thucycides for Alexander I’s son Perdiccas. First, Alexander advises the Greeks on where to make their stand against the Persian army, who “debated, in view of Alexander’s words, as to how and in what country to make their stand to fight the war. The winning option was for guarding the pass of Thermopylae” (History 7.175).

Just as Herodotus tells us of the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae on the advice of a Macedonian, Thucydides describes 300 Macedonians led by a Spartan general defending a narrow pass. Alexander I also attempts to convince the Athenians to make an alliance with the Persians. But the Spartans “had heard that Alexander had come to Athens to bring the Athenians into agreement with the barbarian” and tell the Athenians “do not let Alexander of Macedon convince you with his smooth talk” (8.141-42). In very similar terms, Thucydides describes Perdiccas petitioning the Spartan assembly.

Herodotus also suggests extensive ethnic connections between Macedon and Troy, despite insisting that Alexander was Greek. He characterizes Troy as great colonizers of the Mediterranean, claiming Libyans called Maxyes “are descended from men who came from Troy” (4.191) and noting that Trojans had “crossed over into Europe by way of the Bosporus and subjugated all the Thracians and came down to the Ionian [Adriatic] Sea and as far to the south as the river Peneus” (7.20). The river Peneus drains the country of Thessaly, neighbors of Epirus and Macedon, and is also mentioned in the Iliad. Thus Herodotus suggests that Trojans colonized Macedonia.

While describing Xerxes’ Anatolian army, Herodotus further connects Macedonia to the Phrygians, saying “The Phrygians, as the Macedonians say, were called Briges as long as they were Europeans and lived as neighbors of the Macedonians”. In other words, Herodotus is equating Briges to Epirus, the neighbors of Macedon. He is saying that the Phrygians and Trojans originally came from Epirus. This is the same connection made by Homer in his line about Bellerophon.

He adds, “The Armenians were equipped like the Phrygians, being indeed colonists of the Phrygians”, and “The Lydians [former Phrygians] had arms nearest to those of the Greek style.” Herodotus also claims the Lydians founded Estruscan civilization in Italy, the true local forerunners of Rome. Thus Herodotus is saying that all of ancient civilization, from Italy to Greece to Troy and “Asia”, came from Epirus.

Perhaps most revealing of all, Herodotus says the Mysians “are colonists of the Lydians and are called Olympieni, from the mountain Olympus” (7.74). Olympus is supposed to be in Macedon, it is the homeland of Alexander’s dynasty. But Herodotus says the allies of the Trojans in Homer originally came from Lydia and were called Olympians. Like the Iliad, Herodotus places Olympus in the region of Troy.

And yet a few books earlier, Herodotus strove to claim that Macedonians were Greek, an evergreen cultural controversy. He states flatly, “the descendants of Perdiccas are, in fact, Greeks” (5.22). He also claims Alexander must be Greek because he “proved he was an Argive” to participate in the Olympics (5.22). This is the same controversy that would later surround Alexander the Great, who spread Hellenic culture to India.

According to the mythology of Herodotus, the Lydian king Croesus was informed by the gas sniffing oracle of Delphi that he would destroy a great empire if he went to war against Cyrus the Great - who coincidentally also became the prophesied Messiah of the Jews. Strangely, although Cyrus “defeated” Croesus in the 540s, the Croeseid coins continued to be minted for 30 years. Then in 515 BC, Persian emperor Darius I introduced his own coins based on the ones from Lydia: the biggest pieces of gold yet.

Remember, the date given for the founding of the second Jewish temple by Cyrus coincides exactly with the founding of the Roman Republic. But the world famous temple of this period, the Artemision in Ephesos, was actually rebuilt by Croesus.

Now we will see how Thucydides remakes history yet again.

3. The Strange Alexander of Thucydides

Thucydides correctly infers from Homer that before the Trojan war, there was no widespread Hellenic identity, with most of the Greeks calling themselves Pelasgians. He notes that Homer reserves the adjective Hellenic for followers of Achilles.

Around 400 BC the Greek historian Thucydides tells us about Alexander, forefather of Macedonia, and about Homer’s dubious poetic history, but doesn’t mention Paris. In the same time period, Euripides wrote a tragedy about Paris called Alexandros.

Although Thucydides does not mention Herodotus by name, he pointedly corrects some of Herodotus’s claims and generally disapproves of his mythical style. Like Polybius centuries later, Thucydides enjoys a reputation as a “straight” historian, not inclined to fantasy or religion. But his work still reveals undeniably fictional elements.

Just as the Trojan war began as a conflict between Paris Alexander and the Greeks, and just as the Persian War was mediated by the first Macedonian king Alexander I, Thucydides tell us that the son of Alexander I was responsible for precipitating the Peloponnesian war. Thucydides says the war began when a city called Corcyra on the island across from Epirus, neighbors of Macedonia, beseiged their own colony in further north in Illyrica after it was taken over by Corinthians.

Corcyra is on the island called Corfu in Epirus, near Ephyra as mentioned by Homer. Thucydides says Corcyraeans “boasted of their naval superiority” and claimed descent from famous sailors, adding “Corcyra lay very conveniently on the coastal route to italy and Sicily” (1.44). As Corcyra prepares to fight for its northern colony, Thucydides writes: “This fleet sailed out from Leucas to the mainland opposite Corcyra […] There is a harbor here, and above it, at some distance from the sea, is the city of Ephyre in the Elean district. Near Ephyre the waters of the Acherusian Lake flow into the sea” (1.46). This must be the same Ephyre mentioned by Homer (Ephyra), and the very namesake of Epirus.

Thus a war breaks out between Corinth and Epirus, who had entered into a defensive pact with Athens. They meet in a sea battle near Epirus that Thucydides calls “the biggest battle that had ever taken place between two Hellenic states” (1.50). This was the first cause of the Peloponnesian war.

The second cause of the war was intrigue between Athens and Macedonia. Thucydides says “Perdiccas, the son of Alexander and King of Macedonia had in the past been a friend and an ally, he had now been made into an enemy”(1.57). Athenians allied against Perdiccas with his brother Philip during a power struggle in the wake of Alexander I’s unexpected demise.

In need of material support, Perdiccas “sent his agents to Sparta in order to try to involve Athens in a war with the Peloponnese”. This scene, where Perdiccas invites Sparta to fight Athens, only to be rebutted by Athenian diplomats, is precisely reminiscent of the scene in Herodotus where Alexander invites Athens to join Persia and fight Sparta, only to be rebutted by Spartan diplomats. The Corinthians advise Sparta to invade Attica at once, appealing to them as “the liberator of Hellas” for its role in the Persian war (1.69). Athenians advise keeping the peace.

Thucydides says “The part of the country on the sea-coast, known as Macedonia, was first acquired by Alexander, the father of Perdiccas, and by his ancestors, who were originally Temenids from Argos” (2.99).

“We are compelled to take Thucycides on faith. He left no ground for reexamination or alternative judgment. We cannot control the reliability of his informants, since they are not named. We cannot check his judgment of what was irrelevant, since he omitted it ruthlessly”. There is no alternative history to compare it to. Furthermore, scholars acknowledge that Thucydides was interpolated and edited in the Library of Alexandria after his death.

“The people called Mysians, and Phrygians, who live around the so-called Mysian Olympus, border upon the Bithynians to the south. Each of these nations is divided into two parts. One is called the Greater Phrygia, of which Midas was king. A part of it was occupied by the Galatians. The other is the Lesser, or Phrygia on the Hellespont, or Phrygia around Olympus, and is also called Epictetus.” (12.8.1)

Thucydides acknowledges the scrum of credibility concerning the Trojan world:

“After the Trojan times, the migrations of Greeks and of Treres, the inroads of Cimmerians and Lydians, afterwards of Persians and Macedonians, and lastly of Galatians, threw everything into confusion. An obscurity arose not from these changes only, but from the disagreement between authors in their narration of the same events, and in their description of the same persons; for they called Trojans Phrygians, like the Tragic poets; and Lycians Carians, and similarly in other instances. The Trojans who, from a small beginning, increased so much in power that they became kings of kings, furnished a motive to the poet and his interpreters, for determining what country ought to be called Troy.” (12.8.7)

[I apologize for publishing this in an unfinished state. Please help me drive toward an epic conclusion by posting your thoughts in the comments.]