To understand the long and convoluted history of Jesus Christ, there is no better place to start than with his face. Besides his name, the face of Christ is the most universally recognized, with an iconic beard and beatific androgyny well suited to his reputation as a lover of all humankind. But the fact is, Jesus did not originally have a beard at all. He is depicted in the Roman catacombs dating back to the 2nd century AD as an Apollonian youth with a smooth face, evoking John’s motif of the “good shepherd”, adapted from the earlier pagan imagery of a ram-carrying kriophoros. Jesus is also depicted in other catacombs as Orpheus. Even as late as the sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, 359 AD, Jesus is shown in biblical scenes with a smooth face.

Although mainstream historians argue that the early Christians sought to appeal to pagans and/or hide from their oversight, we might also conclude that early Christians had no idea what Christ looked like. This would be unsurprising since the oldest biography of Christ, the gospel of Mark, is written like a fable and openly muses that the lessons of heaven must be taught in parable. Likewise, the letters of Paul indicate that he experienced a vision of Christ, not that he witnessed the ministry of a preacher or healer. For a long time I thought that there could be no historical Jesus: no Galilean fisherman, no reforming rabbi, no closet feminist and homosexual, no miracle working Essene, just multiple layers of mythology. But then I realized something very surprising might lurk behind the mask of Christ: the face of Caligula.

One of the most important parables in the gospels is that of the “Wicked Tenants” in the vineyard. After the tenants repeatedly refuse to pay the vineyard’s owner, the master sends his own son to collect the rent. But the tenants murder the young man:

“The tenants said to one another, ‘This is the heir. Come, let us kill him, and the inheritance will be ours.’ So they seized the son, killed him, and threw him out of the vineyard. What then will the owner of the vineyard do? He will come and kill those tenants and give the vineyard to others.” -Mark 12:7-8

What if Christ is not just telling a parable about himself, but a parable about Caligula? Just after this scene, the Jewish scribes ask Jesus whether it is lawful to pay taxes to Caesar. Jesus says “Bring me a denarius to inspect,” and asks “whose face is this?” The Jews say that Caesar’s face is on the coin. So Jesus replies “Render to Caesar what is Caesar’s” (Mark 12:13-17). This teaching along with the preceding parable shows the pro-Roman perspective of Mark, justifying the “repossession” of Jerusalem by Titus Caesar ~40 years after Jesus’ death. Julius Caesar was one of the first persons in Roman history to have his face on a coin in 44 BC, a practice continued by the Emperors Augustus and Tiberius in the time of Christ. Christ barely prefigures Caligula on the official timeline, dying less than 7 years before the start of Caligula’s reign. One wonders which Caesar had his face on Christ’s denarius.

Two authors critical to our study of Christian origins are Philo and Josephus. These two Jews give us almost all the information we have on the milieu of 1st century Judaism that somehow spawned Christianity. Yet neither Philo in his works, nor Josephus in his seminal War of the Jews, mention Jesus Christ at all. Philo instead focuses attention on Christ’s twisted doppelganger, the infamous emperor who wanted the Jews to worship him as a living god: Caligula, who was also named Gaius Julius Caesar. Like the original Julius Caesar, Caligula was murdered by an assassin named Cassius. Philo makes it clear that Caligula deserves the death penalty for daring to introduce a statue of himself into the Jewish temple, and indeed he is assassinated just before he can follow through with his plans.

The most peculiar thing about Philo is that he gives all credit for the founding of the Roman empire to Augustus and writes as if Julius Caesar never existed at all. Likewise, he gives all credit for causing a religious and political scandal among the Jews in the 30s AD to Caligula. Like Jesus, who Luke says was 30 when he began his ministry, Caligula was betrayed and murdered at age 29, and although their lifetimes are not perfectly aligned, certain chronological discrepancies suggest that they were deliberately offset from each other by 14 years. This work in progress will trace the literary evolution of Christ as well as the connections to the Caesars that clue us in to a radical reunderstanding of who is hidden behind the gospel. Our most surprising conclusion could be that, like Jesus Christ, Julius Caesar never existed at all. Instead, he is another refraction of Caligula’s officially damned memory.

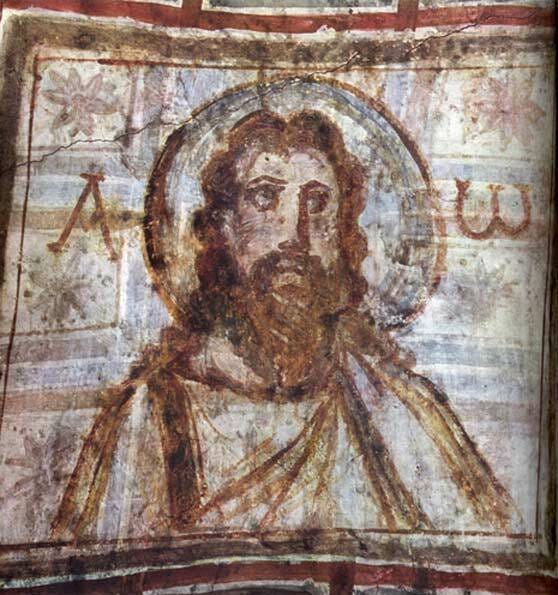

The fictionality of Christ is only proven by the rise of Christian political power in the east, because they abandoned images of Christ as kriophoros and Orpheus only to start depicting him like Serapis. In the catacomb of Commodilla, dated to about 350 AD, Christ is first depicted with a beard. In 391 AD the Christians did something exceedingly destructive and destroyed the Serapeum, the last redoubt of the ancient Library of Alexandria. The Serapeum was dedicated to the bearded god Serapis. After the overthrow of Serapis, Christ began to have a beard full time.

Caligula was also intimately connected to Serapis, credited with the construction of the Iseum Campense in Rome, a temple to Isis and Serapis, said to have originally been voted by the Second Triumvirate in 42 BC. Dio describes Caligula’s facial hair, like Christ’s, subject to sudden change: “He would make up first with smooth chin and later on as a bearded man.” Likewise Philo describes Caligula as dressing up as any number of pagan gods and parading around in their costumes. One wonders if he ever dressed as Orpheus, like Christ in the Roman catacombs.

Serapis was intimately conjoined with the Library of Alexandria; both were commissioned by Ptolemy I Soter, the first Hellenic pharaoh of Egypt circa 300 BC. Serapis was a deliberately syncretic deity, combining aspects of the Egyptian deities Osiris and Apis with classical humanistic representation of Zeus and Hades, uniting the religion of Egypt with that of its new overlords. The cult of Serapis was promoted by the Ptolemies as a state religion, and it later spread throughout the Roman empire, with temples in Greece and Rome. Serapis was known as a healer as well as a universal sovereign, aspects that passed neatly over to Christ. The cult of Serapis declined exactly in concert with the legalization of Christianity by Rome. And so the fresh faced shepherd boy became the more dignified Pantocrator.

The Library of Alexandria figures prominently in the evolution of Christ, because sometime around 250 BC, it published the Jewish bible in the Greek language, a book known as the Septuagint, offering the oldest evidence of Jewish scriptures. The main personalities associated with the roots of Christianity—Philo as the exponent of the Logos and allegorical interpretation of scripture, Paul as the first advocate of Jesus Christ, and Josephus as the historian of Jerusalem’s karmic downfall—all depended on their Septuagints to understand the Jewish history and prophecy that Jesus Christ is said to fulfill. The most primitive Christ, found in the letters of Paul, is not apparently based on a real person at all. But he is based on the Jewish prophecies.

Paul is the clear point of origin for Christianity; his letters are the most primitive Christian documents. Analysis of Philo shows he has so much in common with Paul that they could actually be the same person. Like Christ and Caligula, their lives overlapped significantly. Philo became known as the pioneer of allegorical interpretation of scripture, a practice that would be followed by Paul and fully articulated and endorsed by Mark. Philo pitches Judaism to a Hellenic audience, relying on Platonic concepts such as the Logos to weave together Jewish and Hellenic thought. Likewise, Paul preaches a new understanding of Judaism to the Gentiles. Christianity would build on Philo’s idea of the Logos as the word and representative of God; John would eventually tell us that Jesus Christ is the Logos made flesh.

And then there is Josephus. Writing some 30 years later than Philo, after the fall of Jerusalem in 70 AD, Josephus became the court historian of the conquering Roman emperors, the Flavian dynasty founded by Vespasian. The catacombs of Domitilla were built beginning in the 2nd century AD on property owned by the granddaughter of Vespasian, who had triumphed in the Roman civil war of 69 AD before turning his fury on Jerusalem. The Flavian conquest of Jerusalem has deep Christian connections: Josephus argued that the event served as the Roman fulfillment of Jewish prophecy, while the gospels foreshadow the destruction of Jerusalem as Jesus prophesies “not on stone will be left upon another”. According to the theses of Joseph Atwill, the gospel narrative itself was invented by the Flavians. Thus, it should come as no surprise that the earliest Christian art comes from Flavian family tombs.

The problem with giving priority to Julius Caesar is that much of Roman myth and history is modeled directly on Greek literature. Thus although Caesar was supposedly born exactly 100 years before Christ, their mutual resemblance tells us that one was based on the other. Their names are practically identical, first name beginning with the name of God (Jesus/Jehovah vs Julius/Jupiter), last name which is synonymous with the title of a divine king. Both are renowned for their mercy and liberality; both made themselves enemies of the Senate/Sanhedrin who suspects them of wanting to usurp the authority of the council. Jesus comes from Galilee, etymologically related to Gallia (Gaul) where Caesar campaigned before before crossing the Rubicon, just as Jesus crosses the Jordan on his way to Jerusalem. Both rise to heaven after being betrayed before they can assume their throne. Worship of one replaces the other.

Julius Caesar was supposedly deified by the Roman senate in 42 BC, creating the imperial cult that would be enjoyed by Augustus and later ruined by Caligula. Not coincidentally, no statues of Caesar as Divus Iulus survived Christian iconoclasm, thus we cannot verify whose face was originally worshiped. Yet statues of Augustus, including the “Prima Porta” which features Cupid, and the statue of Augustus from Herculaneum in which he is posed like Jupiter, survive untouched. Christianity became the direct alternative to emperor worship, leading Rome to accuse Christians of atheism and treason, before Christianity became the religion of Rome and began their centuries long persecution of pagans and heretics alike.

To start at the deepest roots of Christianity, we will travel back in time to 250 BC to understand the Jewish prophecies that were then published in Greek. We will progress to Philo and Paul as the parent(s) of Christianity and the cataclysm that befell the Jews after Vespasian won the Roman civil war. We will examine Josephus as the forerunner of Mark and the other gospels, and the resulting tug of war between Jewish and Roman sympathies. We will analyze Matthew as satire and Marcion as docetism, plus John as a special plea to the Gnostics and Luke and Acts as outright fraud. We will follow the beardless, symbolic Jesus out of the Roman catacombs to the legalization and state empowerment of Christianity in the east, the wickedly inventive pen of Eusebius, the co option of the bearded Serapis, and the orgy of book burning and iconoclasm that ensued to defend the literal historicity of what originated as imaginative literature. And then we will use a little math to show Christ = Caligula.

Read more:

The Mysterious Martyrdom of Polycarp

Christianity’s early chain of custody passes through a pivotal figure named Polycarp who, like Paul, wrote a letter to the Philippians. Unlike Paul, however, Polycarp was familiar with and quoted from the gospel of Matthew. Polycarp’s apprentice Irenaeus became the first person to name and reference all the gospels in

Fascinating to read about the history of the face of Jesus Christ. Also very interesting that the fate of the Library of Alexandria is intertwined with the beginnings of Christianity. I'm intrigued!

A lot I've never heard of here. Nice read.